Introduction

On 27 August 2015, I found myself wandering through Marudi, a quiet riverside town in northern Sarawak that once stood as the gateway to the vast Baram interior. Though time has slowed the pace here, traces of Sarawak’s colonial past still stand firm — the most striking being Fort Hose, built during the Brooke administration.

As I walked through the fort and its small museum, I could still feel the weight of history — the stories of explorers, missionaries, local chiefs, and the Bungan religious movement that reshaped the beliefs of the Kayan and Kenyah people in the 1950s.

1️⃣ Fort Hose – A Colonial Stronghold (Built 1 Nov 1901)

Named after Charles Hose, the British officer and explorer who served under the Brooke regime, Fort Hose was completed on 1 November 1901. It served as both an administrative and defensive outpost during a time when the Brooke government sought to consolidate control over upriver territories.

Standing in front of the fort today, the structure’s white timber walls and black accents evoke a sense of timeless authority. The pair of rusting cannons guarding its staircase are remnants of an era when the fort symbolized British presence and “civil order” in the interior.

Inside, it has been converted into a mini museum, housing photos, ethnographic exhibits, and stories of the people who lived through the early 20th century transformations in Baram.

2️⃣ The Birth of the Bungan Movement (1950s)

Inside the museum, I found a fascinating display about the Bungan religion — a movement that emerged among the Kayan and Kenyah people during the mid-20th century.

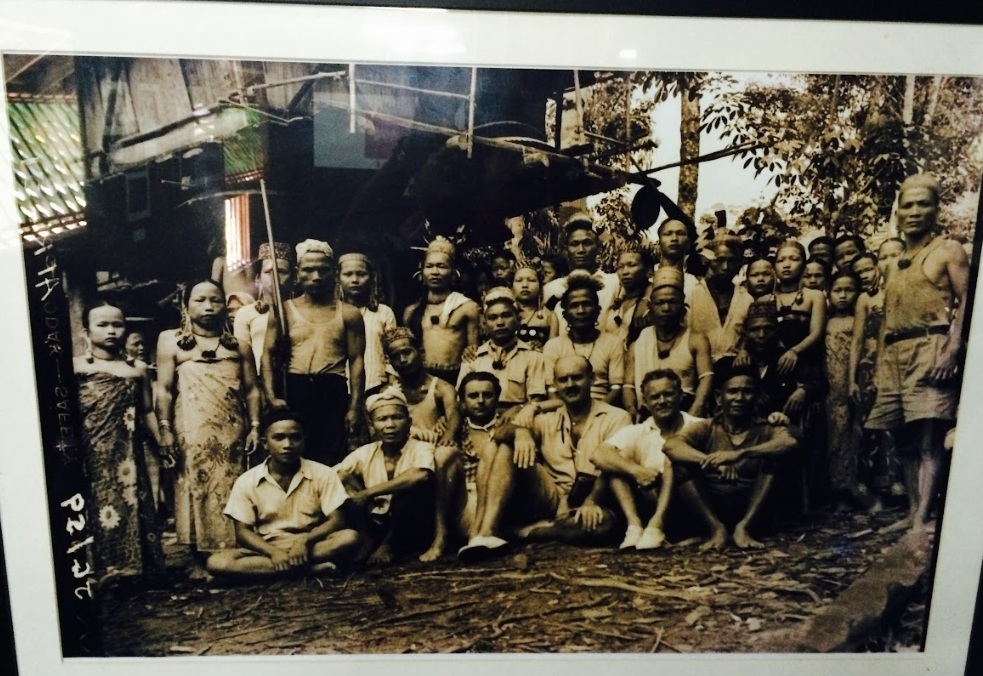

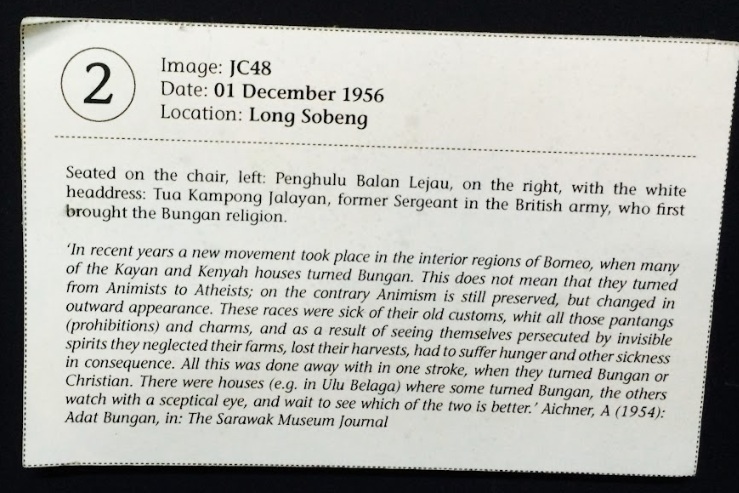

According to the museum label (dated 1 December 1956, Long Sobeng):

“Seated on the chair, left: Penghulu Balan Lejau… on the right: Tua Kampong Jalyan, former Sergeant in the British Army, who first brought the Bungan religion.”

This new faith was a turning point in the cultural history of Borneo. As quoted from the Sarawak Museum Journal:

“In recent years, a new movement took place in the interior regions of Borneo, when many of the Kayan and Kenyah houses turned Bungan… These races were sick of their old customs, with all those pantangs (prohibitions) and charms… All this was done away with in one stroke when they turned Bungan or Christian.”

Essentially, the Bungan movement was a religious and cultural reform, rejecting restrictive animist taboos while maintaining spiritual beliefs. It became a bridge between old indigenous traditions and the new worldviews brought by missionaries and colonial administrators.

3️⃣ Glimpses from the Past

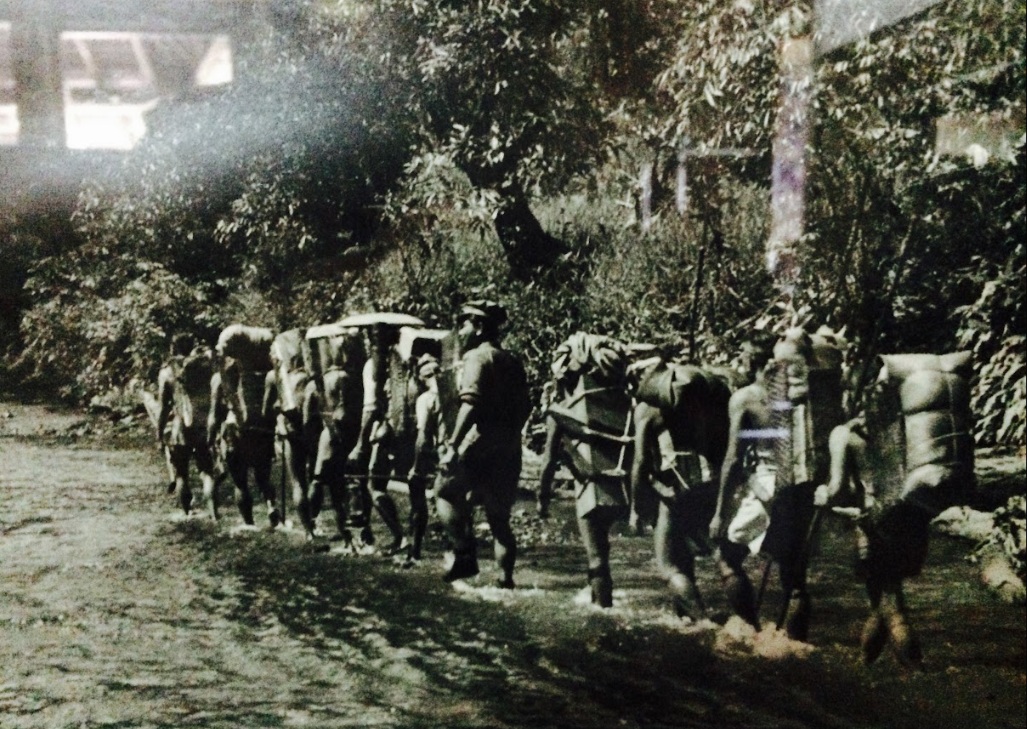

The sepia-toned photographs displayed within Fort Hose show life as it once was —

-

a longhouse meeting, where elders and chiefs discussed matters of faith and survival;

-

a group portrait of local Kayan and Kenyah men and women, proudly standing beside visiting British officers;

-

and a caravan of porters carrying supplies through jungle streams, reminiscent of the long treks between settlements like Marudi, Long Lama, and Long Sobeng.

Each frame feels alive — the eyes of the people tell stories of resilience, transition, and coexistence during a turbulent but transformative time.

4️⃣ Marudi Today – A Quiet Guardian of History

Today, visitors land at the small Marudi Airport, welcomed by a sign that reads “Selamat Datang ke Marudi.” Though modest, this town once served as the administrative and trading hub for the entire Baram region before Miri rose to prominence.

Marudi Town has changed tremendously over the past 10 years. It is connected by a bridge of which was only accessible by boat or aeroplane.

Walking around Marudi, you can still sense its old-world rhythm — wooden shophouses, the slow flow of the Baram River, and the enduring Fort Hose watching over it all.

Conclusion

My visit to Marudi in 2015 wasn’t just another stop in northern Sarawak — it was a quiet encounter with history. The cannons, the fort, the photographs, and the voices of the past preserved in the museum remind us how much this land has evolved, and how the people of Baram balanced tradition and change.

Fort Hose may no longer guard the river as it once did, but it continues to protect something far greater — the memory of Sarawak’s cultural transformation.